Tales of Blood and Gods: Some Thoughts on Religion and Race

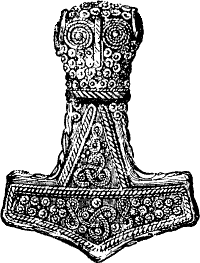

Mjolnir, the hammer of Thor; one of the major symbols of Ásatrú.

“How strangely things grow, and die, and do not die! There are twigs of that great world-tree of Norse belief still curiously traceable.”

Thomas Carlyle, Lectures on Heroes, 1841

I come from a long line of atheists, heretics, and breakers of convention. I’m skeptical about anything related to what’s considered the paranormal or supernatural. I don’t think I've ever held an honest religious belief. I consider myself, above all, to be an ardent rationalist. I look for facts, I weigh evidence, and I attempt to come to measured conclusions.

Despite this, I've never had a problem with religion qua religion. I like the idea that there is more to our existence than what can be seen, and I am happy for any collection of sky-searchers to worry about my soul so long as those who believe in their chosen deity or deities refrain from interfering in my “real” interests. A Muslim in Riyadh can dictate to the females around him as he pleases; it doesn't concern me. It does concern me, however, when that Muslim wishes to import his beliefs and attending actions (not to mention about one hundred equally ‘pious’ relatives) into my locality.

Closer to home, I can’t say I've had much of a problem with Christianity among my fellow Whites. In fact, I have a number of Christian friends; as a group they’re a polite bunch, and normally seem quite cheerful. A few of them had struggled with depression and myriad social difficulties until they “found Jesus,” so perhaps there is something to be said for the palliative benefits of that faith; and perhaps this explains, more than any other fact, its endurance and appeal in all ages.

However, controversial though it may be to say it, it occurs to me that Christianity is coming more and more into conflict with what I perceive to be my interests and those of my ethnic group. Curiously, for a religion which grew like a weed from the rabidly ethno-centric soil of Judaism, Christianity has been anything but a friend to the ethnic group which breathed life into it, energized it for centuries, and took it to the four corners of the earth. The source of almost unceasing fratricidal conflict for centuries, the Church now reveals itself a party to the abolition of the European peoples. In the past, when Europe, North America and other White nations were ethnically homogenous (and confidently so) some of the fundamental conflicts between ideas of the “universal man under God,” and an acknowledgement that one was part of a specific ethnic community with concrete interests, could be masked. Not so in this brave new world. Only since the 1950s can we assess the utility of the Christian faith in acting as a boon to the folk who for centuries granted it lordship over them. And in the assessment of this writer, it has been found wanting. . . .