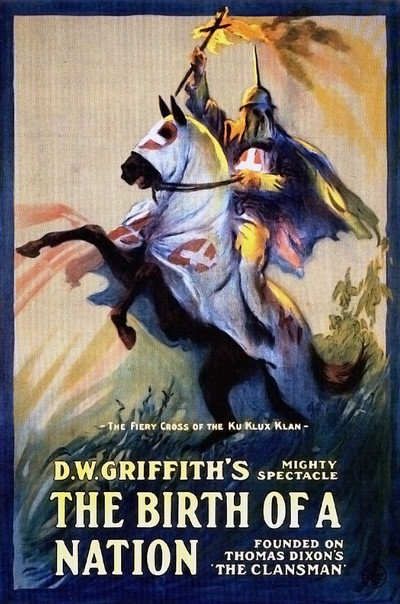

“Birth of a Nation” at 100 Years Old

Liberals and multiculturalists hate it when confronted with works of obvious genius which don’t fall into the pattern of their worldview. Along with angst-fuelled hand-wringing over certain works by Shakespeare and Wagner, a more modern manifestation of the problem is the cinematic landmark, The Birth of a Nation, which will quietly celebrate its centenary this week. Compelling, innovative, trend-setting, and epic in scale, D.W. Griffith’s astonishing and unflinching vision of the Civil War and Reconstruction-era South remains powerful viewing even on its hundredth birthday.

I was an impressionable eighteen-year-old college student when I first viewed it. Despite the admonitions and careful commentaries of my film and media professor, I remember seeing past the fact that it was silent and interspersed with grainy captions and being impressed by its ‘modern’ style and appearance, and the smoothness of the editorial process. But it was some years later before I came to truly appreciate the scale and meaning of what Griffith had committed to film. On this occasion I watched it in North Carolina, at the home of my wife’s very elderly grandfather. This remarkable old man was every inch a Southerner, and a true gentleman at that. There one humid May evening, with the AC broken down and the windows wide open, the old man pulled out some Civil War relics that he had collected over the years. Presenting a series of antique rifles, medals, and pictures of Lee and Jackson, his eyes regained a youthful spark as he spoke of his own family memories and connections (real or imagined) to a host of Confederate heroes. Later in the evening, after we set down the relics of war in favor of cigars and Scotch, he pulled out a dusty VHS from an old bookcase. It was Birth of a Nation. It’s a long movie, clocking in at over three hours, and the old man drifted off to sleep within the first half hour. But I kept watching. And it was that night, with the firebugs glowing and buzzing by the open windows, and with the fragrant Southern air drifting slowly inside, that I felt what Griffith had aimed to portray — pride of land, pride of culture, and pride of blood. ...